The Chomsky Apparatus

Our Library and the Intellectual Architecture of Manufacturing Consent

Preface: The Unlocked Door

This is not a book review. It is a trial.

The defendant is not a man, but a function. The function is the management of dissent. Its brand name is Noam Chomsky.

The prosecution is not presented in the language of the salon, but in the language of the colonized: the forensic language of the stolen library and the ignored deed, the dialectical language of Mehdi Amel, the seeing revolutionary language of Ghassan Kanafani.

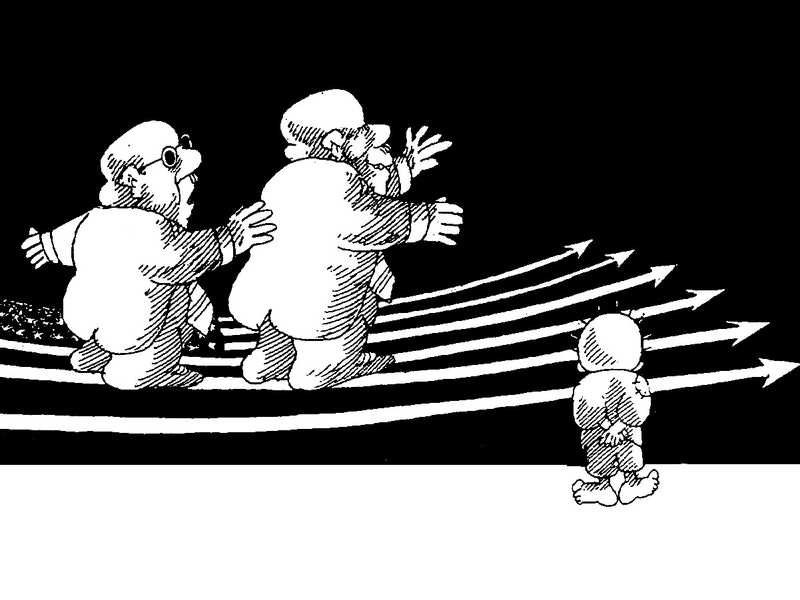

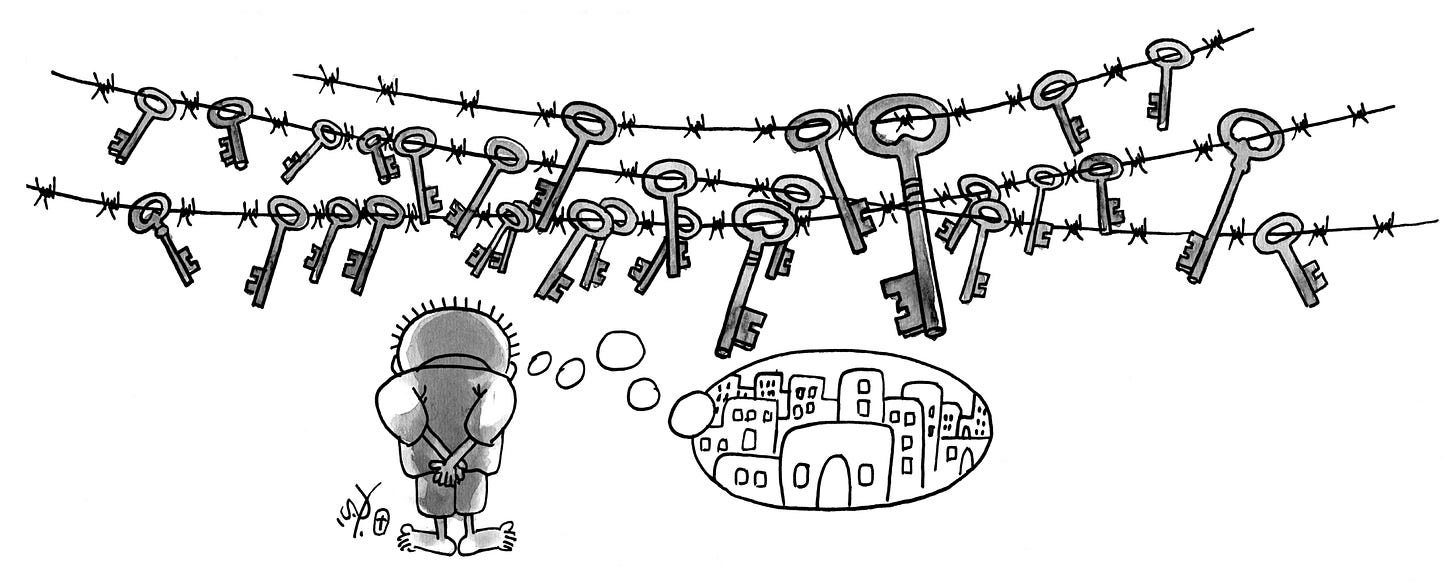

From the perspective of these Organic Intellectuals, to not have this trial would be a sign of theoretical decay, strategic capitulation, and moral failure. It would allow a powerful, seductive form of left-wing confusionism to continue unchallenged—misdirecting generations of would-be revolutionaries into a cul-de-sac of critique that changes nothing. For us Palestinians, this is not merely intellectual work. It is custodianship. It is our task to stand guard at the door of our own narrative, to refuse the keys offered by those who would lock us into their managed dissent. This paper is conceived in that spirit—an act of guardianship.

As such, this text is an act of intellectual sovereignty. It refuses to argue on terms set by the empire’s most useful critics. It will not “engage generously” with a body of work whose ultimate social effect is to sterilize revolutionary impulse. It will not chase the nuances of a theory that, at its core, is designed to be apolitical.

Instead, it performs a forensic extraction. It isolates the DNA of Privileged Intellectual Anarchism and follows its expression through linguistics, through politics, and ultimately to its logical, moral terminus: semi-zionism. It demonstrates how these form a coherent apparatus—not through conspiracy, but through the cold logic of political class position.

This argument is architectural. It is built to bear weight. To follow it requires you to hold multiple strands of evidence—historical, theoretical, biographical—in mind at once. It demands you accept, if only for the duration of this reading, that the authority of the martyred theorist outweighs the authority of the tenured professor.

You will be tempted, at many points, to object. You will think: This is unfair. This is reductive. What about his good work? These objections are not merely your own. They are the immune response of the very ideology being dissected. The text anticipates them not by listing rebuttals in a preface, but by building a case so structurally sound that the objections crumble against its foundation.

This text will be misread. It will be used to claim Palestinians reject all solidarity. To be clear: we reject solidarity that demands we negotiate our erasure. We embrace solidarity that aligns with our liberation. Distinguish between the two.

To those who would use this critique to claim we “accept nothing”: your accusation only confirms that you value the critic’s comfort over the colonized’s freedom. Our standard is not purity—it is alignment. The question is not whether you criticize the occupation state, but on which side of the prison gate you stand.

If you require “balanced” take or comfort thinking, turn back. These are the creeds of the neutral—a luxury afforded only to the unoccupied.

If you are ready to see the bridge of radical critique for what it is—a magnificent structure that leads only back to the prison gate—then turn the page.

— ‘Amel-Ba’al

“- I will stay here.

- for how long?

- forever, does forever seem far away to you?”

—Ghassan Kanafani.

“It is self-evident that the intellectual must be revolutionary or cease to be.”

“For the first time in the history of thought, revolutionary theory merged with revolutionary movement. Thought, in its cognitive activity, aligned itself with the forces of change.”

“Culture, by definition, is resistance. If it equates the killer and the killed, it is defeated in its nihilism, and the killer triumphs, with culture, in its silence, as his accomplice.”

“There is no contradiction between politics and culture… In the perspective of science and history, politics is a comprehensive class struggle across all fields of life, with no margin for those who, in illusion, refuse to take a position within it.”

“Revolution is not a word or an abstraction. It is the mud of the earth, unknown to those who fear soiling their hands.”

“Culture flowed in a struggle between two: one, the culture of the masters, with its diverse and conflicting currents, and the other, the culture of the oppressed, in its various forms.”

—Mehdi Amel.

For a long time, these words sat like a shard of my grandfather’s house key at the bottom of a well—a heavy, silent weight. To speak them in the open air of this empire felt like offering my family’s last deed to a court that recognizes only the bulldozer and the civilizing gospel of the racist occupier. We Palestinians know the cost of naming things correctly in a world that profits from their erasure.

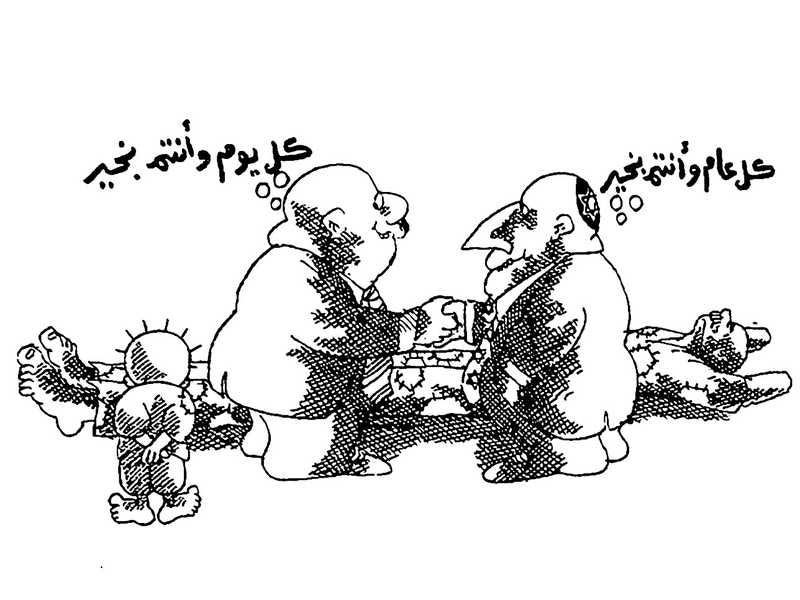

To take aim at Noam Chomsky here, in the West, is to invite a special weather. Not the open violence reserved for our resistance, but the cold, dismissive drizzle of the liberal salon: “But he’s on your side. He’s the good one. Did you read his awesome and amazing books? Who are you, anyway?” It is the violence of being told, once again, to be grateful for the crumbs of a critique that stops at the threshold of our actual freedom.

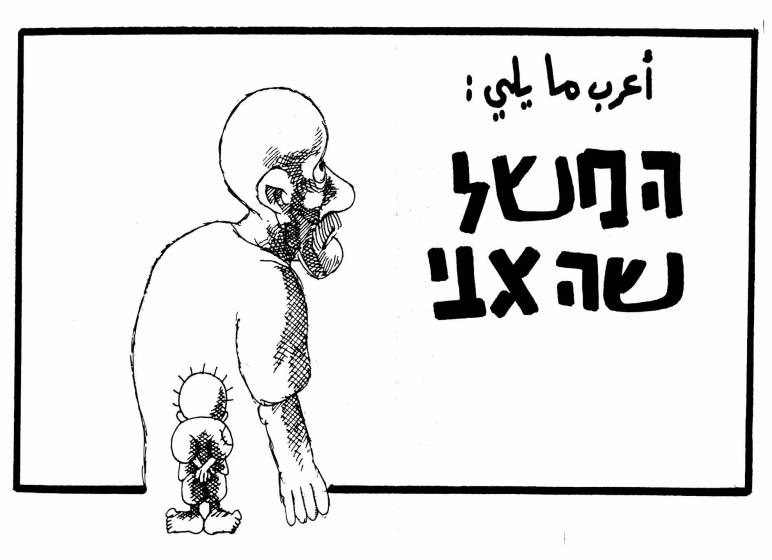

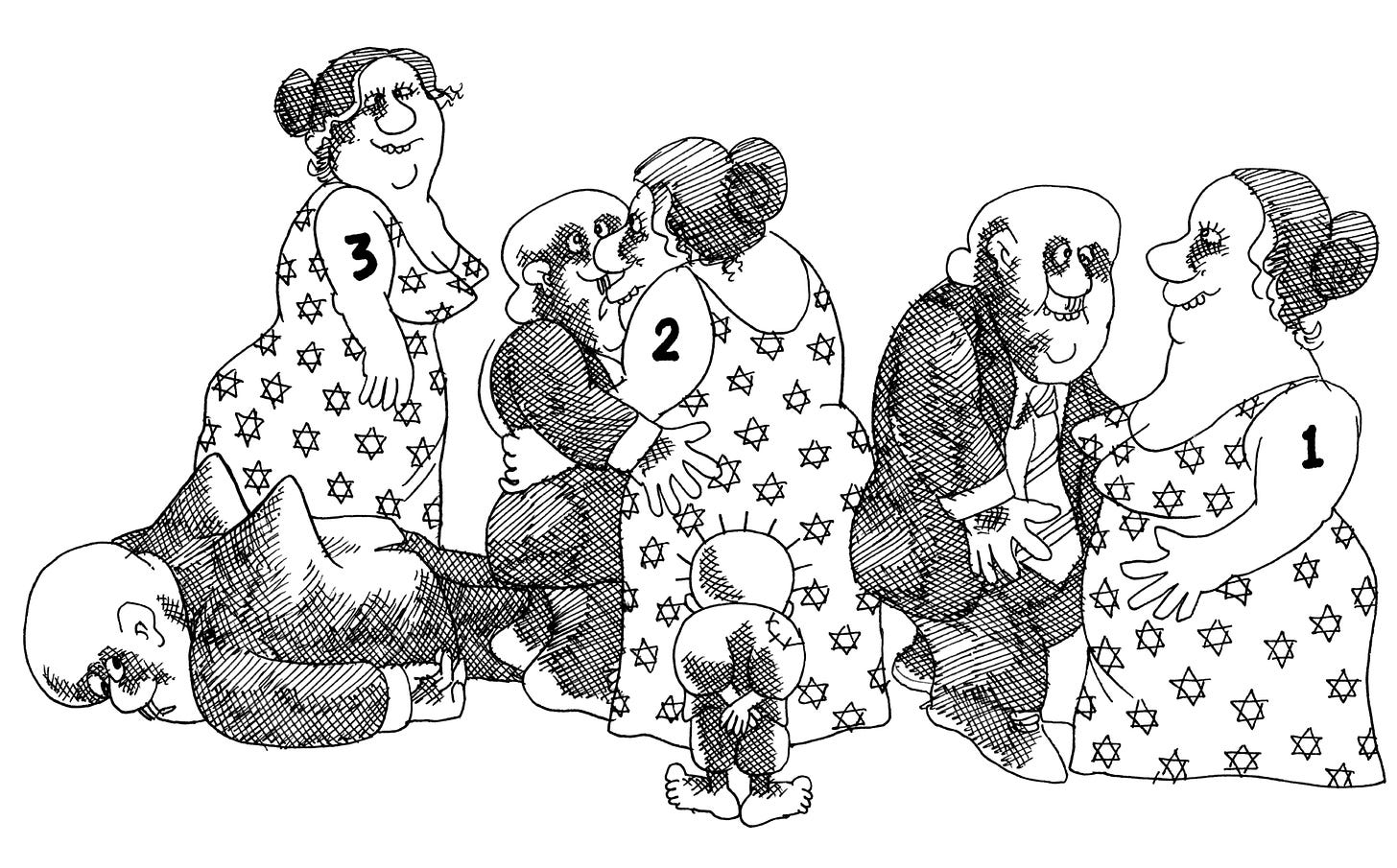

So I drew it up. I polished it in the dark with the stories of our icons they attempted to erase—Kanafani, Amel, al-Ali—and the teachings of our land.

Then I saw a picture. Him, Noam Chomsky, in the house of the predator Epstein. Smiling, relaxed, with Steve Bannon—a man whose political vision, like that of his zionist host, is a death sentence for our people. In that space, among monsters, the “radical” critic and the fascist shared the same light, the same air, the same smile. This was not a coincidence. This was the address. This is the room where the management of dissent is calibrated. Where the radical posture is laundered in the company of those who would see our people erased. While our elders rot in occupation prisons and our children dig through rubble for food, their rebellion is a theory debated over wine in a zionist and pedophile’s mansion.

That picture was the crack. It said: He does not live in our world. He lives in theirs. His words are a bridge they built for people like us to walk on, so we never learn to think.

And I knew then what I had always known: this man who sat comfortably among monsters would never stand unambiguously with us. How could he? His entire intellectual project is a fence. Take my own family’s library—our library. It was a living thing. It breathed with the smell of manuscripts from the 14th century, of my ancestors’ handwritten books. It was not a collection; it was a root system. In 1948, the zionist gangs and land-robbers came. They did not burn it. What they did was colder and sinister. They cataloged it. They boxed it. They shipped it to the vaults of the “Hebrew University” in Occupied Jerusalem—a citadel of the very settler-colonial project that massacred and erased hundreds of villages, now turning our living history into curated artifacts for its academy.

This is not a metaphor. It is a theft. A literal, ongoing theft of memory, of proof, of history. The colonial thieves call it “preservation.” The people of the land call it the continuation of the Nakba by other means. They silence our past to invalidate our present.

And Noam Chomsky, the great critic of power, is against the academic boycott of this rogue settler-colonial, apartheid state? Of the institutions that polish these stolen treasures and call them their own—or worse, declare them ownerless? He took the same position against the boycott of apartheid South Africa. His argument is always the same: for “dialogue” and “engagement” with the very machinery that systematically erases us, that turns our heritage into their prize.

You see it now. His position is not an inconsistency. It is the final, perfect proof. His linguistics provides a theory that cannot name colonial theft. His politics provides a dissent that cannot endorse the tools that might stop it. And his “pragmatism” on Palestine demands we negotiate with the thieves while they hold our family albums, our deeds, our very words in their locked, genocidal archive.

The man from Epstein’s table sees no contradiction in “engaging” with a military occupation state and apartheid regime. Of course he doesn’t. The bridge he built only travels in one direction: toward accommodation, never toward principled struggle. Boycott is principled struggle. It is a material, collective “no” that shatters the illusion of normalcy. It demands a side be chosen. He, an American intellectual, will not choose that side. He will only critique from a distance that changes nothing.

So here. Take this key. It is not made of theory. It is forged from the iron of our people’s exile and the fire of their betrayal, from the dust of our stolen libraries. This is not a critique from within their salon. It is a testimony from beneath its floor.

Let it be entered into the record.

The record reads as follows.

“To admit a mistake frankly, to ascertain its reasons, to analyze the conditions that led to it, and to thrash out the means of its correction—that is the hallmark of a serious party; that is how it should perform its duties, how it should educate and train the class, and then the masses.”

Lenin, “Left-Wing” Communism: an Infantile Disorder (1920)

Introduction: The Architecture of a Managed Radical

The anarchist movement did not begin as a weapon of the state—but over time, its deepest tendencies made it into one. What presents itself as radical refusal has, through a long and concrete historical process, evolved into a disorganizing force that attacks revolutionary discipline while providing radical cover for empire. No figure embodies this evolution more than Noam Chomsky, whose “anti-authoritarian” posture did not arise in a vacuum. It emerged in a specific moment, when the state was actively searching for ways to split the Left, and its practical effect—regardless of intent—has been to systematically undermine revolutionary socialist movements while advancing narratives that align with state counter-revolutionary goals.

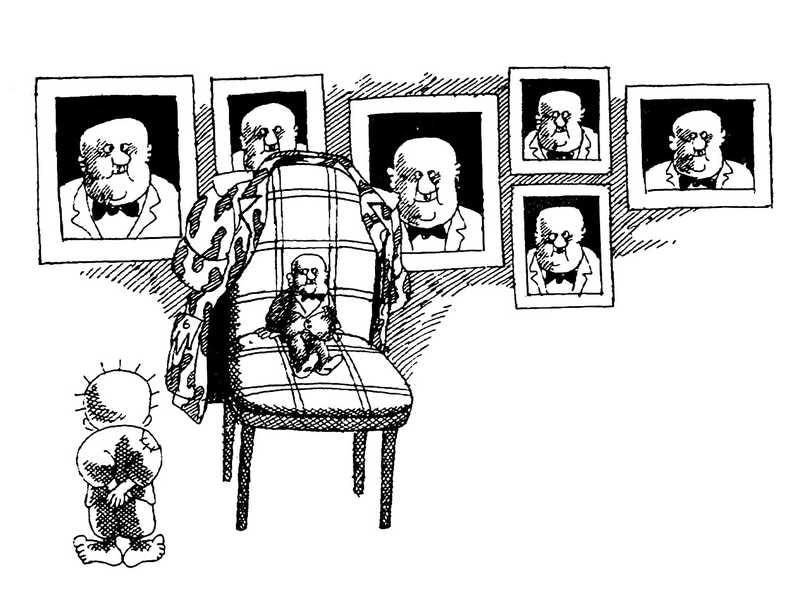

This is not a historical accident but the logical terminus of a specific class formation: Privileged Intellectual Anarchism. We must distinguish between the anarchism of the oppressed—the spontaneous anti-statism of the peasant, the syndicalist impulse of the exploited worker—and the anarchism cultivated within the professional-managerial strata of the imperial core. The latter is not born of material desperation but of a subsidized alienation; its radicalism is funded by the very imperial system it rhetorically opposes, transforming revolution from a collective, disciplined project of seizing power into a performance of individual moral critique. Chomsky’s career embodies this privileged variant: the revolutionary shell of anarchism emptied out, leaving only its perfect utility for disorganizing the Left from a position of tenured safety.

This is not a simple story of personal failure or intellectual inconsistency. It is the story of an apparatus—an interconnected intellectual system whose components function to produce a specific, state-tolerable outcome: the manufacturing of compliant dissent. To examine these parts in isolation is to miss the design of the whole. Together, they form a coherent architecture for managing consent, an architecture that has made Chomsky not a threat to power, but one of its most sophisticated and useful critics.

Dear Anarchists in the belly of the empire, if you truly oppose hierarchy, take a look at this “anarchism” that drinks wine with the architects of hierarchy.

“The intellectual forces of the workers and peasants are growing and getting stronger in their fight to overthrow the bourgeoisie and their accomplices, the educated classes, the lackeys of capital, who consider themselves the brains of the nation. In fact they are not its brains but its shit.”

— Lenin, A Great Beginning (1919)

Part I: Privileged Intellectual Anarchism as Imperialism’s Left Flank

COINTELPRO’s Discovery: How Fragmentation Becomes a Tool

Declassified FBI files reveal less a conspiracy invented from nothing than a strategic recognition of an existing weakness. A 1968 memo observes: “Anarchist elements are the most disruptive in the movement… Their opposition to structure can be exploited to create internal divisions.” The state did not create anarchism; it identified, amplified, and weaponized its inherent vulnerabilities, particularly those of its privileged, intellectual expression which naturally recoiled from the discipline of an avant-gardist party.

The tactics were a mirror held up to this anarchism’s own tendencies. FBI field offices produced fake anarchist publications like The Workshop, which attacked revolutionary socialist groups as “authoritarian” while promoting a depoliticized focus on “underground cinema, sex, and dope” (FBI San Francisco, 1969). As Ward Churchill documents in The COINTELPRO Papers, the Bureau flooded circles with literature that reframed revolution as “personal liberation” rather than collective struggle. Most tellingly, they amplified anarchist critiques of the Black Panther Party’s organizational discipline—turning the Left’s own internal debates into fatal fractures.

This was not simple repression. It was the deliberate cultivation of a certain kind of dissent: one that felt radical but remained manageably fragmented. And in this context, Chomsky’s intellectual project—developed in parallel, not in secret coordination—became the perfect philosophical complement. His work gave scholarly dignity to the very impulses the state was promoting within Privileged Intellectual Anarchism: suspicion of organization, preference for moral protest over strategic action, and a deep discomfort with disciplined revolutionary parties.

Chomsky’s Evolution: From Critic to Complementary Force

Chomsky did not set out to serve power. But the internal logic of his position—his philosophical commitment to a form of privileged individualism disguised as anti-authoritarianism—steadily pulled his work into alignment with state interests. His 1981 text Radical Priorities dismissed the Black Panthers’ discipline as “authoritarian,” language indistinguishable from FBI memos seeking to discredit the Party.

During the Vietnam War, his emphasis on “moral protest” over material solidarity with the Vietcong channeled anti-war energy into academic discourse rather than revolutionary action. This analytic stance—which substitutes psychological diagnosis for partisan alignment—was crystallized in a later reflection. In a 1989 interview with David Barsamian he framed the era’s ferment, listing “the Viet Cong, the Black Panthers, the students, the bearded Cuban revolutionaries, the Maoists,” as part of a “threat to privilege” stemming from “partially paranoid fantasies” of the powerful. In a single phrase, he performed the essential function of his apparatus: transmuting a class struggle into a psychiatric condition. The revolutionary is reduced to a phantom in the bourgeois mind.

This analytic distance, which understands rebellion only as a symptom of elite paranoia, made his concluding observation inevitable. He noted: “Again, Israel came along and showed how to use violence effectively in restoring order, and that was an impressive demonstration. It was particularly important for Liberal humanists, because Israel was capable, with its very effective propaganda system, of portraying itself as being the victim, while it very efficiently used force and violence to crush its enemies.”

Here, the function of the apparatus is laid bare. The anarchist critic, so adept at diagnosing the master’s fears and admiring the master’s tools, reveals his foundational respect for the settler-colonial state’s capacity not only to crush ferment but to narrate its crushing as victimhood. The Palestinian, the crushed enemy, disappears entirely from the analysis, which is concerned only with the impressive mechanics of power and its liberal perception.

This early pattern—diagnosing revolution as elite psychology and admiring colonial order—hardened over decades into a predictable function. Today, his support for Rojava’s Kurdish anarchists—a movement that operates under Pentagon air cover while fracturing Syrian sovereignty—updates the role for a new imperial moment. The 1977 debate with Foucault exposed the core of his thought: when pressed on strategy, he retreated into abstract appeals to “human nature” and dismissed class struggle as “too deterministic.” It was a performance of Privileged Intellectual Anarchism that ultimately defended nothing but the right to critique—a function the state has always been willing to tolerate, and at times encourage.

The relationship is not one of direct conspiracy, but of complementary development. As the state worked to fracture revolutionary movements from without, Chomsky’s brand of Privileged Intellectual Anarchism, indirectly, eroded them from within, each reinforcing the other’s effects until the original impulse of resistance was reshaped into a force that sustained the very system it claimed to oppose.

Why Privileged Intellectual Anarchism Was the Perfect Vehicle

The state did not choose anarchism at random. It selected its privileged intellectual variant because this form’s class nature—its roots in the salaried professionals and academics of the imperial capitalist—made it structurally incapable of posing a revolutionary threat. Privileged Intellectual Anarchism rejects the instrument required for victory—the disciplined revolutionary party—not on strategic grounds, but on existential ones: its adherents’ social location depends on the stability of the institutional landscape they claim to oppose. Their militancy is confined to the realm of discourse. In the 20th century, proletarian or peasant anarchism collapsed into heroic defeat. In the 21st century, under a sophisticated imperial hegemony, Privileged Intellectual Anarchism achieves something else: assimilation into the machinery of managed dissent. Chomsky’s role mirrors what Gramsci identified as the traditional intellectual’s function: to articulate hegemony while appearing to oppose it.

Chomsky’s work is the perfected form of this assimilation. It provides a radical-sounding philosophy for a professional class that wishes to critique power from a position of safety and comfort, without engaging in the concrete, perilous work of building a counter-hegemonic force. Where the FBI promoted “lifestyle radicalism” to replace political organization, Chomsky offered “consumer activism” and intellectual critique as alternatives to party-building. Where the state needed left cover for imperial interventions, Chomsky provided it—whether for Rojava or for anti-Soviet dissidents dressed in anarchist rhetoric.

This convergence was not accidental; it emerged from the material reality that Privileged Intellectual Anarchism, in the imperial core, could imagine opposing power but never actually theorize to overthrow it. Thus, over time, the appearance of radical “confrontation” gave way to a function of managing dissent. Five decades of Chomskyite “resistance” have produced endless books and lectures but zero revolutionary threats to capital. Meanwhile, every successful anti-imperialist movement—from Cuba to Vietnam—has relied on the disciplined organization that privileged anarchists scorn. The pattern reveals the completed transformation: anarchism began as a critique of authority and ended as the state’s preferred form of “opposition”—a resistor for revolutionary current.

The Tolerance of Power: What Survival Reveals

The state’s treatment of different strands of the Left exposes the real stakes. While Black socialists like George Jackson were assassinated and revolutionaries like Fred Hampton were murdered in their beds, Chomsky’s books fill corporate bookstores; MIT, a pillar of the military-industrial complex, housed him comfortably for decades. The contrast is a material lesson: the state exterminates what it fears, and tolerates—even promotes—what it can use.

Chomsky himself once articulated this lethal calculus with unnerving clarity. Reflecting on why the FBI’s assassination of Fred Hampton was excluded from the Watergate scandal, he observed:

“But at the very same time that the enemies list came out, it was revealed in court hearings that the FBI had been involved in an outright political assassination of a Black Panther organizer, Fred Hampton. Did that show up in the Watergate hearings? No... Because if the state is involved in a gestapo-style assassination of a Black Panther organizer, that’s OK. He has no power, and he’s an enemy anyway. On the other hand, calling powerful people bad names in private, that shakes the foundations of the republic.”

Here is the state’s counterinsurgency logic, diagnosed by its most celebrated critic: the revolutionary organizer is a threat to be murdered; the critic who “calls powerful people bad names” is a spectacle whose dissent proves the system’s tolerance. The devastating irony is that Chomsky does not see he is describing the mechanism of his own safety. He names the rule—revolutionaries get bullets, critics get a platform—while being its primary beneficiary. The state murdered Fred Hampton for building a revolutionary organization. It features Noam Chomsky for theorizing why such organizations are flawed. His immunity is the confirmation of his function.

COINTELPRO murdered Fred Hampton, drove Assata Shakur into exile, and has kept Mumia Abu-Jamal imprisoned for over forty years. Chomsky, meanwhile, became a celebrity academic—and a welcome guest in a zionist billionaire’s house. This material disparity—between the safety of the critic and the martyrdom of the revolutionary—lays bare the ultimate class function of Privileged Intellectual Anarchism. The state understands, in a way some “leftists” still refuse to, that abstract criticism changes nothing, while organized revolutionary capacity changes everything.

Consider the ultimate material test of this ideology. Anarchism, in its revolutionary conception, is a philosophy for the abolition of hierarchy and the concentrated, predatory wealth that enforces it. Its logical end is the dismantling of the capitalist state and the expropriation of the billionaire class. Therefore, an anarchist who is a regular and comfortable guest in a billionaire’s house is, by the incontrovertible logic of his own situation, not an anarchist at all. He is performing a role. The mansion is not his target; it is his context. His ideology is not a threat to that world; it is a curated feature of its intellectual landscape. The state does not violently silence such a critic because it recognizes in his “radicalism” a perfectly managed form of dissent: one that critiques the furniture but never dreams of bringing down the house.

Privileged Intellectual Anarchism is allowed to flourish precisely because it poses no threat to the foundations of power. It is the radicalism of those who have a desk in the empire’s house. Where revolutionary socialists get bullets, sacrosanct anarchists get book deals—and the ruling class sleeps soundly knowing the difference.

Beyond the Fairy Tale: Confronting the Real Enemy

We are left with a choice—but not simply between two ideologies. It is a choice between a politics that remains at the level of appearance—of radical posture and endless critique—and one that grasps the material process of how power is actually seized and transformed.

When the Black Panthers built breakfast programs and armed self-defense, they triggered a genocidal repression from the state. When Chomsky writes another book critiquing “American exceptionalism,” the state yawns. The FBI understood this. The Panthers understood this. Only within the circles of Privileged Intellectual Anarchism does the fairy tale persist: that structureless resistance can somehow dismantle the most violently organized empire in history.

The way forward is not to reject every impulse that anarchism represents—the hunger for freedom, the distrust of bureaucrats—but to transcend its privileged, disarming form. It is to build a movement that learns from history: that understands discipline not as authoritarianism, but as the necessary counterpart to lasting liberation; that sees the state not as an abstract evil to be denounced, but as a concrete force to be overthrown by a collective more organized, more strategic, and more rooted in the masses, the working class, the colonized, the super-exploited. The path ahead is not the one Chomsky has walked. It is the one the state has tried, repeatedly and brutally, to destroy.

“Man’s consciousness not only reflects the objective world, but creates it.”

— Lenin, Philosophical Notebooks.

Part II: The Epstein Letter – The Forensic Autopsy of an Apparatus

The Stolen Document as Confession

This is a forensic extraction. The subject is a single unsolicited text: the 2005 letter of Noam Chomsky in defense of Jeffrey Epstein. We do not treat this as biography. We treat it as evidence entered into the record of a much larger crime—the crime of managed dissent. In his own polite, academic prose, Chomsky provides the most damning testimony against himself. The letter is a map—not of theory, but of material and moral geography. It charts the coordinates of a mind that inhabits the world of the predator, not the world of the oppressed. Here, in plain English, is the blueprint of Privileged Intellectual Anarchism: radical critique as a subsystem of empire, valued, tolerated, and stimulated by the very forces it claims to oppose.

1. The Grammar of Submission: “A Most Valuable Experience”

The opening establishes the relationship not as a struggle, but as a transaction of deference. “I met Jeffrey Epstein half a dozen years ago… It has been a most valuable experience for me.” The subject is not a people, a cause, or a liberation struggle. It is a billionaire financier. The value extracted is not from sumud, from resistance, from the mud of the earth. It is from association. This is the language of the client, the junior partner, the grateful beneficiary. It establishes, in the first breath, the foundational truth: the anarchist critic does not stand against hierarchy; he stands within it, looking gratefully upward.

2. The Anarchist’s Tutor: A Curriculum in the Logic of Capital

Chomsky details his education. His teacher is not the refugee, the prisoner, or the martyr. His professor is the oligarch. “I have learned a great deal from him about the intricacies of the global financial system… Jeffrey invariably turns out to be a highly reliable source, commonly going well beyond what I can find in the business press.” Here, the “anti-capitalist” linguist confesses to being a pupil of the capitalist machine. Epstein is not analyzed, not critiqued, not named as a node in the network of predation. He is a superior source, a translator of the arcane for the tenured academic. This inverts the entire claimed posture. Power is not the target of critique; it is the author of the critic’s syllabus. The “anarchist” linguist is, in material practice, a dedicated student of the oligarchy, his analysis refined in the predator’s private seminar.

3. The Concierge of Empire: Radicalism as a Guided Tour

The letter celebrates not Epstein’s ideas, but his utility: his function as a gatekeeper to the powerful. “Jeffrey has repeatedly been able to arrange, sometimes on the spot, very productive meetings with leading figures… Once, when we were discussing the Oslo agreements, Jeffrey picked up the phone and called the Norwegian diplomat who supervised them, leading to a lively interchange. On another occasion, Jeffrey arranged a meeting with former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, whose record I had studied carefully and written about. We have our disagreements, but had a very fruitful discussion about a number of controversial matters.“ This is the operational core of the apparatus. Access to empire is not a corrupting temptation; it is a concierge service.

The radical critic does not confront power; the billionaire facilitates his visit. “Lively interchanges” replace moral and intellectual judgement. This transforms political dissent into salon radicalism—a performance staged in green rooms and private libraries, mediated by a fixer whose wealth is built on the exploitation the critic elsewhere denounces. Here, the ultimate function is laid bare: the anarchist critic is granted a “fruitful discussion” with a principal author of Palestinian suffering, our “controversial matter,” courtesy of a zionist financier to the elite. The “disagreements” are academic; the access is material. The Palestinian, for whom Barak is not a debating partner but a Prime criminal and historical antagonist, disappears from the room entirely. The anarchist enjoys the fruits of the very settler-colonial and financial networks his ideology nominally seeks to dismantle.

4. The Personal Covenant: “A Highly Valued Friend”

Professional admiration crystallizes into a bond that annihilates all moral posturing. “He quickly became a highly valued friend and regular source of intellectual exchange and stimulation.” This is the sentence that demolishes the defense. This is not acquaintance; it is active, sustained valuation. It proves that Chomsky’s famed moral calculus registered no fatal contradiction. The machinery of his critique and the machinery of Epstein’s predation were not in conflict; they were in productive, stimulating symbiosis. The letter provides material proof: the social world of the West’s most useful critic comfortably included its most grotesque enablers. The cognitive dissonance that should shatter a conscience was, for him, merely the hum of interesting conversation.

The Letter as the Engine’s Service Manual

The Epstein letter is not an anomaly. It is the concentrated transcript of the apparatus at rest in its natural habitat. It exposes the class function: the parasitic symbiosis between the privileged critic and the financier, each using the other to validate his own worldliness—the critic gains access, the predator gains intellectual cover. This is the petty-bourgeois dream: radicalism without risk, critique without consequence. It documents the political impotence of this dissent, showing its highest form of “action” to be the facilitated meeting, its “struggle” a dialogue with power. It is, as Kanafani would diagnose, the ultimate blind language: radical vocabulary emptied of all strategic content, all capacity for rupture. Most crucially for our liberation struggle, it reveals the moral bankruptcy of “pragmatism.” The man who would later, from the safety of MIT, lecture Palestinians on their need for “pragmatic policies” and to abandon “absolute justice,” demonstrated his own pragmatism here: it is the opportunism of the comfortable. His morality is flexible for himself—valuing a friendship with a monster—but rigid and demanding for the colonized—negotiate, dilute your rights, be “reasonable.” His entire posture on Palestine—the semi-zionism that bargains with the blueprint of our erasure—is prefigured in this letter. He is, and always was, a negotiator with power, not an ally of those who seek to break it.

From Reference to Indictment

Therefore, this letter transcends its purpose. It is no longer a character reference for a predator. It is Chomsky’s own unwitting indictment. He has written, in clean academic prose, the service manual for his apparatus: how it is powered by access, programmed by the elite, and what it truly values—the stimulation of managed dissent within the mansion of power. This document is the material evidence that his anarchism is a philosophy of the guest wing, not the barricade. All that follows in this analysis—his linguistics of deliberate silence, his semi-zionist pragmatism that betrays our cause, his policing of resistance—is merely the elaborate intellectual superstructure. This letter reveals the foundation: a profound comfort among predators, and a personal, intellectual debt to the very world they rule. It is the key that was never meant to be found, proving the door to his radicalism opens only into the warden’s parlor.

The Apparatus in Real Time: The 2020 Interview – From Personal Covenant to Public Defense

The 2005 letter revealed the apparatus at rest in its natural habitat: a private correspondence of gratitude and intellectual debt. But an apparatus is not static; it is a living system that activates to defend its own integrity. A 2020 interview, given after Epstein’s death and the exposure of his crimes, captures the apparatus in its public operational mode—performing the management of dissent in real time.

Faced with a direct question about Epstein’s impunity, Chomsky does not reflect on his own past judgment, express solidarity with the victims, or interrogate the networks of elite complicity. Instead, he executes a flawless series of maneuvers that confirm every diagnostic feature of Privileged Intellectual Anarchism:

The Immediate Pivot to ‘Greater Crimes’ (The Glass House Doctrine Applied):

“Jeffrey Epstein gave a million dollars to MIT. Is he the worst person who’s contributed to MIT?... I saw the David Koch Cancer Center... one of the most extraordinary criminals in human history.”

Here is the “glass house” logic, live. The specific, grotesque criminality of a child sex trafficker within the elite is immediately universalized and relativized. The focus is deflected from the particular network (Epstein’s world of finance, intelligence, and academia) to a safer, more ideologically convenient target (the Koch brothers, climate change). The function is clear: to transmute moral outrage into a generic systemic critique, draining all energy from pursuing accountability for the specific predators and enablers in Epstein’s circle. It is not that Koch’s crimes are lesser; it is that this pivot protects the topology of power Chomsky’s own 2005 letter placed him within.

The Procedural Dodge and Asymmetric Skepticism:

When pressed on the bizarre, suspicious circumstances of Epstein’s case (the intelligence link, the disabled cameras), the apparatus retreats to agnosticism:

“I haven’t followed it closely... there’s no real way of answering that question... with the information we have.”

Contrast this with his categorical condemnation of David Koch. For the right-wing villain, certainty is allowed. For the crimes that touch the heart of the elite establishment—the intelligence agencies, the plea deals for billionaires—the posture is one of cautious, procedural skepticism. This is the “pragmatic” brake applied precisely where inquiry might become dangerous, revealing the class-based limits of his radical curiosity.

The Weaponization of Abstract Principle:

He offers a defense in the form of a liberal legalistic principle:

“after serving the sentence he’s the same as everybody else... seems to be forgotten.”

In this context, the principle is a surreal and inhuman abstraction. Applied to a billionaire who orchestrated a lenient plea deal for trafficking minors, it becomes a rhetorical shield for the powerful. The anarchist critic, who theoretically opposes all state power, here deploys the state’s own most cynical legal fiction to deflect scrutiny. It is a performance of “fairness” that functions as a defense of impunity.

From Private Gratitude to Public Defense

The 2005 letter showed the apparatus’s foundation: a class symbiosis between critic and financier, a personal debt to the predator’s world.

The 2020 interview shows the apparatus’s immune system: when that world is threatened with exposure, it activates not with remorse or self-criticism, but with a sophisticated, automatic protocol of deflection, relativization, and procedural obfuscation.

Together, these two documents form a perfect dialectical proof. The private letter reveals why he is compromised; the public interview reveals how that compromise expresses itself ideologically. The man who was a “highly valued friend” to Epstein in private becomes, in public, his most sophisticated philosophical defender—not by denying the crimes, but by rendering them irrelevant through the vast, neutralizing machinery of “systemic critique.”

The apparatus does not conspire; it functions. And here, its function is laid bare: to ensure that no matter how damning the evidence, the conversation is always shifted away from the concrete complicity of the elite and toward the abstract, safe, and politically manageable terrain of generalized condemnation. It is the ultimate demonstration that his radicalism is a pressure valve, not a weapon—a system designed to absorb and dissipate shock, never to allow it to strike at the heart of the house he gratefully inhabited.

“Social-Democratic phrases and fatuous wishes; and petty-bourgeois revolutionism—menacing, blustering and boastful in words, but a mere bubble of disunity, disruption and brainlessness in deeds.”

— Lenin, The Crisis Has Matured (1917)

Part III: On Linguistics – The Unspoken Foundations of Colonial Science

The ascent of Noam Chomsky in the field of linguistics coincided with the consolidation of a political project his theory was uniquely equipped to analyze—yet never did. The discipline he helped shape was already organized according to antiquated and racialized categories, categories that served to divide peoples into civilizational lineages. And while he deconstructed the architecture of grammatical rules, he left untouched the colonial foundations upon which the very idea of the “Semitic family” was built—an idea that did not merely classify language but helped prepare the ideological ground for political claims to land and origin. His silence was not an oversight but the logical outcome of a theoretical framework that treated language as a biological abstraction, separate from the historical and political forces that shape its use and meaning.

The Uncontested Heritage: “Semitic” as a Colonial Category

The idea of a “Semitic” language family did not emerge from neutral scientific inquiry. It was the product of European intellectual currents seeking to order the world according to the biblical narrative and a racial hierarchy. In the late 18th century, scholars like August Ludwig von Schlözer refashioned the story of Noah’s son Shem, turning theological genealogies into a linguistic-racial classification. This framework grouped a retroactively constructed “Hebrew,” Arabic, and Aramaic together, implicitly portraying their speakers as sharing a distinct racial destiny, separate from and often opposed to the “Aryan” West.

This classification solidified during the 19th century, becoming a cornerstone of Orientalist studies. It created a term—”Semitic”—that could be filled with contradictory political content. For some, it signaled a primitive, uncreative spirit; for others, like early zionists, it provided a scientific pretext for asserting an essential link between European Jews and the geography of the Eastern Mediterranean, despite the complex, dispersed reality of Jewish communities. This category never faced Chomsky’s famous skepticism. He inherited it as a neutral, technical given, a classificatory box whose political history and consequences remained outside the scope of his formal analysis.

Theoretical Abstraction as Political Evasion

Chomsky’s revolutionary focus—the search for universal grammatical rules innate to the human mind—required stripping language of its social substance. By centering the “ideal speaker-listener” in a “completely homogeneous speech-community,” his model consciously bracketed out history, power, and identity. This was a methodological choice with profound political implications. It rendered the messy, often violent realities of language imposition, suppression, and revival—the very dynamics at the heart of the zionist settler-colonial project—marginal to the core scientific endeavor.

Thus, when zionism engineered “Modern Hebrew” as a “national” language, consciously displacing the Yiddish of Ashkenazim and the Ladino and Arabic heritage of Sephardic and Arab Jews, it presented a perfect case study of language as a political weapon. But from a Chomskyan formalist perspective, this could be seen merely as an instance of innate grammatical capacity acquiring a new lexicon. The colonial character of the project—the systematic devaluation of Palestine’s Arabic dialects (which preserve ancient Canaanite phonetic features), the severing of Mizrahim from their literary heritage, the fabrication of a continuous “revival” narrative—faded from view. His theory contained no vocabulary for linguistic colonialism because it had deliberately excluded society from its equation.

The Gap Between Capacity and Action

The true measure of Chomsky’s failure is not that he invented tools of oppression, but that he withheld the critical tools his position and intellect could have forged. He stood at the intersection of multiple worlds: a linguist of transformative influence, a scholar at MIT (where adjacent work in genetics was complicating simplistic racial-linguistic maps), and a public intellectual famed for dissecting propaganda. From this vantage point, the contradictions were stark: the politically charged myth of a unified “Semitic” people versus the genetic and historical record; the colonial construction of “Modern Hebrew” versus its narrative of natural birth; the active erasure of Arabic.

His personal politics—his critiques of Israeli policy, his advocacy for a binational state—remained entirely separate from the linguistics he practiced. He never applied the analytical rigor he leveled at U.S. foreign policy to the founding myths his own discipline had helped naturalize. He could have illustrated how linguistics has been weaponized throughout history, how terms like “Semitic” were laden with colonial assumptions. He could have used his platform to amplify scholars challenging these constructs. Instead, he maintained the partition, protecting the “scientific” core of his field from the “political” contamination of its applications and history. In doing so, he granted silent assent to the ideological status quo.

The Legacy: A Disciplined Silence

The result is a stark duality. In one realm, Chomsky the political commentator critiques power. In the other, Chomsky the linguist—through omission—provides a kind of academic sanctuary for the very narratives power uses to justify itself. Zionism’s claim to land relies heavily on a story of linguistic and historical continuity, a story built upon the uncontested category of the “Semitic.” By refusing to interrogate the dubious origins and political utility of this category, Chomsky’s work allowed it to retain a veneer of scientific neutrality.

This is not a betrayal by a conscious collaborator, but a more insidious failure by a fragmented thinker. It reveals how radical critique can coexist with deep conservatism within one’s domain of expertise. The man who taught a generation to question everything their government said simultaneously taught them to accept, without question, the inherited colonial architecture of his own science. In the end, his linguistics did not actively make zionism, but its disciplined silence on the political life of language helped preserve the ground upon which zionism’s myths could stand unchallenged from within the academy. The most devastating critiques often come not from what is said, but from what a theory is structurally designed to ignore.

Thus, we arrive at the unforgivable contradiction of the Chomsky Apparatus. The public intellectual, hailed as our foremost demystifier of power, constructed a scientific discipline deliberately mystified—purged of history, struggle, and theft. He gave us a theory of language that could describe the grammar of a sentence but remained intentionally useless for describing the grammar of a genocide: how a “Semitic” label is pasted over a stolen land, how a “revived” imaginary tongue is used to silence a real living one, how an archive is cataloged to bury a people.

This is not a minor academic disagreement. It is a failure of the highest intellectual order. For a scholar who stakes his reputation on connecting political acts to their systemic causes, to refuse to connect the colonization of Palestine to the colonial architecture of his own field is an act of either staggering bad faith or profound cognitive dissonance. It reveals the final function of his celebrated “rigor”: to provide a radical alibi for a mind that willfully averts its gaze from the foundations of the very power it claims to critique. We are asked to celebrate the whistleblower who stands in the hallway shouting about a fire, while he politely ignores that the hallway itself is built on the ashes of our home. A scholarship that chooses to be blind to the political life of its own most basic categories is not radical. It is, at best, a form of academic malpractice; at worst, it is the intellectual wing of the theft it claims to oppose.

Chomsky, the radical linguist, is not the user of language for liberation, but the manager of language for pacification, the brilliant linguist who says nothing with his semantics, and his systemic phase cancellation. He is the electrician who wires dissent so it never completes the circuit.

“People always have been the foolish victims of deception and self-deception in politics, and they always will be until they have learnt to seek out the interests of some class or other behind all moral, religious, political and social phrases, declarations and promises.”

— Lenin, The Three Sources and Three Component Parts of Marxism (1913)

Part IV: On the Real Question, Palestine – The Semantics of Semi-Zionism

Noam Chomsky’s posture on Palestine is that of a master engineer who can disassemble the engine of empire with one hand while insisting, with the other, that the vehicle it powers must remain on the road. He will furnish you with every schematic, every metric of fuel consumption and heat dispersion, every record of the collisions it has caused. But he will never tell you to get out of the car, to dismantle it for scrap, to imagine a road that does not belong to it. His critique is exhaustive, yet his conclusion is one of surrender: the machine is too large, the road too entrenched, the passengers too accustomed to the ride. We must instead, he argues, recalibrate the steering, install better brakes, negotiate a slower speed.

This is the essence of Chomsky’s semi-zionism: a radicalism of diagnosis married to a liberalism of prescription. It is a stance forged in the furnace of post-1967 left politics, where the sheer, undeniable brutality of the occupation demanded a response from Western conscience. Zionist settler-colonialism, having achieved territorial conquest through war crimes and genocide, now needed to manage the public relations disaster of its permanent military occupation rule and institutionalized apartheid. It required a language that could absorb the shock of criticism without yielding an inch of soil.

Chomsky, the linguist, became a primary supplier of that language. He offered the disaffected liberal a way to condemn Israel’s actions without condemning Israel’s existence, to oppose the occupation without opposing the colonial logic that birthed it. His work constructed a sophisticated pressure valve, channeling moral outrage into the safe conduits of academic critique and doomed diplomatic advocacy, forever redirecting energy away from the foundational, revolutionary demand: the dismantling of the settler-colonial project itself.

But history keeps its own records. While Chomsky speaks in the abstract language of “state rights” and “international systems,” the founders of the zionist project spoke in the concrete, unvarnished language of settler-colonial planning. They left us not theory, but testimony; not ambiguity, but blueprints. Their archived words—from private diaries to internal committee reports—form a canon of intent that stands in brutal contradiction to the narrative of tragic necessity and pragmatic accommodation. To read them is to realize that Chomsky is not analyzing a struggle; he is negotiating with a ghost, bargaining over the terms of a crime whose perpetrators left a signed confession.

1. The Confession: Premeditation And Transfer As Policy, Not Tragedy

The core of Chomsky’s moral compromise rests on a specific historical framing: that the Palestinian catastrophe of 1948 was a “tragedy” born of war, a messy, perhaps criminal, but ultimately contingent event from which we must now move forward. The zionist colonial archive annihilates this framing. It reveals the Nakba not as a chaotic byproduct of conflict, but as the execution of a long-premeditated demographic strategy, articulated with chilling clarity years before a single tank rolled.

Consider the voice of zionist Polish David Gruen (Ben-Gurion), Israel’s founding prime criminal, in 1944. This is not the cautious diplomat speaking for international audiences, but the strategist defining the mission for the inner circle:

“Zionism is a transfer of the Jews. Regarding the transfer of the Arabs, this is much easier than any other transfer.”

The statement is a syllogism of dispossession. First, zionism is defined in its essence not as a spiritual return or a cultural revival, but as a process of human “transfer”—the movement of Jews into Palestine. Second, and with cold, operational logic, the necessary corollary is stated: the transfer of Arabs out is not a lamentable side effect, but an integral, even facilitated, component of the same project. It is “much easier.” The word choice is not accidental. It speaks of logistical convenience, of a problem with a ready solution. This is not the language of tragedy; it is the language of a technician discussing an engineering schematic. Four years before the war, the leadership’s mind was not on whether transfer would happen, but on how efficiently it could be achieved.

This was not a lone opinion. It was the consensus of the apparatus. Yosef Weitz, the director of the Jewish National Fund’s Lands Department and a key figure in the “Transfer Committee” of 1948, wrote in his diary in 1940:

“There is no other way than to transfer the Arabs from here to neighboring countries, all of them. Not one village, not one tribe should be left… The transfer must be directed at Iraq, Syria, and even Transjordan… For this goal funds will be found… And only after this transfer will the country be able to absorb millions of our brothers and the Jewish problem will cease to exist. There is no other solution.”

Read this and then listen to Chomsky speak of “tragedy.” Weitz outlines a complete program: the totality of the removal (“all of them”), the method (“transfer”), the destinations (neighboring Arab states), the financing (“funds will be found”), and the explicit purpose: to empty the land for the exclusive settlement of Jews. This is a planning document, not a battlefield report. The war did not create the plan; it provided the cover for its implementation. Chomsky’s framework, which treats 1948 as a chaotic origin from which we must pragmatically proceed, is a form of historical blindness. It asks us to build a political solution on a foundation whose architects explicitly intended it to be ethnically cleansed.

The haunting clarity continues. In a 1937 diary entry, David Gruen wrote:

“The compulsory transfer of the Arabs from the valleys of the proposed Jewish state could give us something which we never had, even when we stood on our own feet during the days of the First and Second Temple – a Galilee free from Arab population… We must prepare ourselves to carry out [this transfer].”

Here, the demographic vision is rendered in almost mystical terms—a return to a purified, mythic past achieved through modern bureaucratic compulsion. The goal is not security or coexistence, but a geographic and demographic re-engineering to fulfill an ideological vision. “We must prepare ourselves to carry out” is the language of a commander ordering preparations for a campaign. This is the premeditation that Chomsky’s “tragedy” thesis desperately tries to obscure.

This is the unvarnished calculus of settler-colonialism, spoken in the private tongue of its architects: the native is not a political adversary to be reconciled with, but a demographic problem to be solved. The fantasy, however, is not merely immoral—it is an act of profound, willful bad faith. The ‘Galilee free from Arab population’ Gruen mythologizes was a dream he knew to be false. In 1918, in a book co-authored with Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, he explicitly wrote that the Palestinian Arabs were the “flesh and the blood of the old Judeans.” The settler thus admits, in his own early testimony, the very Indigenous continuity his later politics would require him to deny and violently sever. The dream of a purified Galilee is therefore not a naive historical error; it is a conscious ideological erasure, a required lie for the colonial project to proceed.

To then frame the catastrophic result of this premeditated ‘solution’—the Nakba—as a tragic byproduct of war, as Chomsky does, is not historical analysis; it is ideological laundering of a documented lie. It transforms a program of ethnic cleansing, built on a foundation the cleansers themselves knew was fraudulent, into a vague historical misfortune. Chomsky’s ‘pragmatism’ is thus built on this laundered history, asking the victim to bargain with the terms of an erasure whose very premise is a lie its architects once confessed.

2. The Engine: Colonialism As Cultural Mission, Suffering As Fuel

Chomsky often roots his analysis in a framework of realpolitik and moral critique, implicitly accepting the zionist movement as a sui generis national project responding to unique Jewish suffering. The genocidal, colonial archive again offers a starker, more familiar colonial portrait.

Theodor Herzl, the founder of political zionism, did not see himself merely as a savior of Jews, but as a standard-bearer for European civilization. In a moment of revealing grandiosity, he wrote:

“We can be the vanguard of culture against barbarianism.”

This single sentence places zionism squarely within the ideological currents of late 19th-century European colonialism. It is the language of the French mission civilisatrice and the British White Man’s Burden, transposed to Palestine. The native Arab population is rendered, by definition, as the “barbarian” against which the “vanguard” must advance. This is not a defensive ideology; it is an imperial, racist, expansionist one that justifies genocidal conquest and displacement as a civilizing duty. Chomsky’s critique, which focuses on Israeli military policy and American support, never grapples with this foundational, racist self-conception that made the land seem empty of legitimate owners and ripe for redemption.

Furthermore, Herzl understood the mechanics of his movement with a cold, almost cynical, realism. In Der Judenstaat, he wrote:

“Everything depends on our propelling force. And what is that force? The misery of the Jews… Everybody is familiar with the phenomenon of steam power, generated by boiling water, which lifts the kettle-lid. Such tea-kettle phenomena are the attempts of zionist and kindred associations to check Anti-Semitism. I believe that this power, if rightly employed, is powerful enough to propel a large engine and to move passengers and goods: the engine having whatever form men may choose to give it.”

This is the commodification of suffering. Jewish pain is not merely something to be alleviated; it is analyzed as a potential energy source, a “propelling force” to be harnessed for a political project. The Holocaust did not create zionism, but in Herzl’s logic, it became the ultimate source of fuel for the engine he designed. As he declared: “The anti-Semites will become our most dependable friends, the anti-Semitic countries our allies.” Chomsky, by grounding Israel’s legitimacy in the historical context of the Holocaust while condemning its actions, inadvertently validates this grim utilitarian calculus. He accepts the premise that historical suffering grants political claims, then tries to argue about the limits of those claims. The archive shows that the engine was designed from the start to run on that fuel, and to move in the direction of demographic and territorial conquest.

Herzl’s vision was explicitly colonial in its self-conception. In 1902, he told the Royal Commission on Alien Immigration in London:

“I am not speaking of artificially made colonies, but self-helping colonies, which have that great national idea.”

Here, the settler-colonial project is reframed as “self-help,” erasing the violence of displacement under the banner of national redemption. This is the ideological precursor to the myth of “making the desert bloom”—a narrative that Chomsky’s critique never fundamentally dismantles, because to do so would require rejecting the very legitimacy of the “colony” itself.

That foundational logic was articulated with brutal clarity not by a liberal, but by Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the spiritual father of Likud—considered by contemporaries like Mussolini to be a fascist. He modeled his Betar youth movement on fascist paramilitaries and authored the militant “Iron Wall” doctrine, cutting through any remaining liberal pretense in 1923:

“Zionist colonization, even the most restricted, must either be terminated or carried out in defiance of the will of the native population. This colonization can, therefore, continue and develop under the protection of a force independent of the local population—an iron wall… Zionist colonization must either stop, or else proceed regardless of the native population. Which means that it can proceed and develop only under the protection of a power that is independent of the native population—behind an iron wall, which the native population cannot breach.”

Jabotinsky dismisses the liberal myth of “peaceful settlement.” He states openly that zionism is a “colonizing adventure” that “stands or falls on the question of armed force.” This is not a defensive posture; it is the explicit theory of colonial conquest that the Israeli occupation state has practiced ever since. Chomsky’s “pragmatic” framework, which treats zionism as a national liberation movement gone awry, cannot account for this foundational, militarized colonial logic.

3. The Operation: From Blueprint To Brutal Fact

The archive does not stop at planning. It follows the logic into action, revealing the mentality that governed the catastrophe. Menachem Begin, the future Prime Criminal, celebrating the 1948 massacre at Deir Yassin, declared:

“The Arabs throughout the country, induced to believe wild tales of ‘Irgun butchery,’ were seized with limitless panic and started to flee for their lives. This mass flight soon developed into a maddened, uncontrollable stampede. Of the about 800,000 Arabs who lived on the present territory of the State of Israel, only some 165,000 are still there. The political and economic significance of this development can hardly be overestimated.”

Here, the architect of terror coolly assesses its “political and economic significance.” The panic, the stampede, the mass flight—these are not lamented; they are noted as effective instruments of policy. The ethnic cleansing—the genocide—is a strategic success. This is the reality that Chomsky’s language of “tragedy” and “mistake” sanitizes into meaninglessness.

Even in moments of rare, haunting clarity from within the zionist leadership, the truth breaks through. The leader of zionist terrorist gangs, Moshe Dayan, stated in a 1969 speech:

“Jewish villages were built in the place of Arab villages. You do not even know the names of these Arab villages, and I do not blame you because geography books no longer exist… There is not one single place built in this country that did not have a former Arab population.”

Faced with this settler-colonial archive—a ledger of premeditation, not tragedy—Chomsky’s “pragmatism” is exposed as a form of historical aphasia. He asks us to negotiate with a ghost while holding the ghost’s signed confession.

This is the voice of the foreign occupier acknowledging the totality of the Indigenous erasure. The names are gone, the books are gone, the very memory in the landscape is gone. It is a statement of fact so devastating it encapsulates the entire colonial project: replacement so complete it aspires to oblivion.

4. Chomsky’s Accommodation: Bargaining With The Blueprint

Faced with this genocidal, colonial archive of intent—this unbroken chain from Herzl’s “vanguard” to Gruen’s “transfer” to Weitz’s “solution” to Dayan’s erased geography—Chomsky’s political framework collapses into a form of intellectual bad faith.

His famous formulation that after 1948, the state must be granted “the rights of any state in the international system” is not a pragmatic conclusion. It is a capitulation to the successful execution of a colonial plan. He accepts the fait accompli of genocide as the legitimate foundation for statehood. He translates the violent, premeditated act of “transfer” into the sterile, legalistic language of “state rights.” In doing so, he performs the final, crucial service for zionism that Herzl himself foresaw: he provides the left-intellectual guarantee of legitimacy. Herzl sought “legal, international guarantees” from empires. Chomsky provides moral and intellectual guarantees from the realm of radical critique.

When Chomsky argues for a “binational” or “secular democratic” state as his preferred but “impractical” solution, while advocating a “rotten” two-state solution as the only “pragmatic” path, he is not outlining a strategy. He is managing despair. He is offering a discursive maze that forever postpones the clarity with the archive’s central truth: that the zionist project, by its own founders’ definitions, is structurally incompatible with justice for Palestine’s natives. A “binational” state imagined with the perpetrators of transfer is a fantasy. A two-state solution with a political settler-colonial entity whose foundational ideology, as stated by war criminal Menachem Begin in 1947, is that “The Partition of Palestine is illegal. It will never be recognized… All of it. And for Ever,” is a mirage.

Another Russian zionist war criminal, Ariel Sharon, would later confirm this logic in 1998: “Everybody has to move, run and grab as many hilltops as they can to enlarge the settlements because everything we take now will stay ours… Everything we don’t grab will go to them.” The settlement project is not an obstacle to the “two-state solution”; it is the one-state solution—an apartheid state from the river to the sea. Chomsky’s “sensible path” demands Palestinians negotiate for a state on the fragments of land the colonizer hasn’t yet grabbed, while the colonizer’s ideology explicitly aims to grab it all. It is not a path; it is a trap.

Thus, the documented, premeditated plan for ethnic cleansing—a plan the founders called “transfer” and ‘a miraculous clearing’—is, in Chomsky’s final analysis, rinsed of its genocidal specificity and dissolved into the bland soup of realpolitik: “all states are horrible.” The apparatus’s function is complete: the uniquely eliminatory settler-colonial project is transformed into just another regrettable entry in the ledger of state power.

Chomsky asks Palestinians and their allies to negotiate with the ghost of David Gruen, to bargain over percentages of a homeland whose complete usurpation was the original goal. He critiques the severity of the occupation while accepting the legitimacy of the house built on the ruins of Palestinian villages. This is not solidarity; it is the administration of defeat. It is telling the victim of a premeditated crime to accept a plea deal because the jury has already left the courtroom.

The Palestinian struggle, in its deepest currents, has always understood this. It is not a struggle for better terms within the zionist framework, but a struggle against the framework itself—against the “iron wall,” against the logic of transfer, against the civilizational arrogance of the “vanguard.” It is a struggle that reads the archive not as ancient history, but as a living indictment. It knows that peace will not come from negotiating with a blueprint for your erasure, but from tearing that blueprint to pieces.

This failure is not incidental. It is diagnostic. Palestine is the litmus test for any coherent theory of imperialism. To misunderstand Palestine is to misunderstand imperialism itself.

Lenin, an actual teacher of the oppressed whom Chomsky thinks himself capable of criticizing, defined imperialism as the monopoly stage of capitalism—characterized by the export of capital, the division of the world, and the fusion of state and monopoly power into a system of national oppression. Zionism is imperialism’s perfect specimen: a finance-backed colonial settlement, a military outpost for great powers, a fusion of racial supremacy and capital, and an ongoing project of national dispossession. To see it as anything less—as a “conflict,” a “mistake,” a “tragedy,” or a “border dispute”—is to be blind to the very nature of the system one claims to oppose.

Chomsky’s “anti-imperialism” fails this test catastrophically. His framework reduces imperialism to a policy of aggressive states, not the logic of capital in decay. He chronicles its crimes but cannot name its structure. Thus, his solution is always reformist: better policy, moral pressure, an informed public. He seeks to curb the empire’s excesses, not to seize and dismantle the engine that produces them.

This is why, when faced with the documented premeditation of the zionist settler-colonial project—a plan for transfer written in ink decades before 1948—Chomsky can only offer “pragmatic” negotiation. His ideology has no answer to a colonial blueprint because it refuses the revolutionary conclusion that blueprints must be torn up, not bargained with. He stands forever on the side of imperial management, offering critique as a pressure valve, never as a weapon.

Therefore, his error on Palestine is not one issue among many. It is the exposure of his entire intellectual apparatus. If you get Palestine wrong, you have gotten imperialism wrong. And if you have gotten imperialism wrong, you are not a guide to liberation—you are a manager of dissent. The man who lectures Palestinians on pragmatism from the safety of Cambridge has already chosen his side: he resides in the empire’s house, and his radicalism is a room permitted by the warden. From this condemned room, no key to liberation can be forged. That key lies elsewhere.

True anti-zionism begins where Chomsky’s politics end. It requires:

Denying the Legitimacy of the Colonial Blueprint: Rejecting the premise that a state founded on a premeditated plan of ethnic cleansing and maintained by an “Iron Wall” of force has a “right to exist.” Its existence is the ongoing crime.

Centering the Nakba as an Ongoing Structure: Understanding, as the archive shows, that the Nakba was not a 1948 event but a continuing logic—from the destruction of 500+ villages then to the demolition of homes and olive trees now.

Embracing the Right of Return as the Antidote to Transfer: If the foundational crime was the planned “transfer” out, the foundational justice is the planned “return” of refugees.

Seeing BDS as Strategic Severance: Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions is the material practice of rejecting Chomsky’s “engagement.” It seeks to break the links that normalize the colonial state, applying the pressure he claims only the U.S. can apply—but from below.

Chomsky, for all his volumes of critique, remains forever on the other side of that fundamental line, translating the language of liberation back into the language of accommodation, ensuring the engine he so brilliantly describes continues to run, forever powered by the very misery he claims to oppose.

The colonial archive of zionist quotes is the uninvited witness in Chomsky’s courtroom of pragmatic realism. It testifies to premeditation, to celebratory cleansing, to an ideology of racial supremacy and exclusive ownership. It shows that the “Jewish state” Chomsky asks us to pragmatically accept is, by the admission of its own founders, a settler-colonial project achieved through planned displacement.

Real liberation requires frameworks that look beyond his horizon. It means centering Palestinian futurity over endless negotiation of Jewish identity crises justified by a distorted history. It means following the leadership of Palestinian resistance movements that understand the colonial nature of their oppressor, not debating the “acceptable” forms of zionism in seminar rooms. The choice is, and has always been, stark: either reject all forms of zionist statehood in Palestine as the political embodiment of a documented colonial plan, or admit you are still bargaining with colonialism.

Chomsky, tragically and consistently, has chosen the latter. His legacy on Palestine is that of the brilliant architect who built a magnificent bridge of critique—only to ensure it leads right back to the prison gate of the colonial “international system,” all while convincing those on it that they are moving forward. The archive of zionism shows us the prison’s blueprints. Our task is not to cross his bridge, but to dismantle the prison itself.

“It is particularly necessary to arouse in all who participate in practical work, or are preparing to take up that work, discontent with the amateurism prevailing among us and an unshakable determination to rid ourselves of it. This struggle must be organised, according to ‘all the rules of the art’, by people who are professionally engaged in revolutionary activity.”

— Lenin, What Is To Be Done? (1902)

Part V: The Colonial Relation and the Crisis of the Intellectual – Kanafani, Amel, and the Anatomy of Managed Defeat

The critique of the Chomsky Apparatus does not orbit in the abstract. It is grounded, substantiated, and echoed by a living tradition of revolutionary Arab thought—a tradition that defines itself in diametric opposition to the liberal, reformist, and anarchist tendencies Chomsky embodies. To read Mehdi Amel’s Colonialism and Underdevelopment alongside Ghassan Kanafani’s writings on the 1936–39 revolt, on “blind language,” and on the dilemmas of the resistance is to hold up a mirror to Chomsky’s project. It reveals him not as a flawed ally, but as the organic intellectual of imperial liberalism—a thinker whose function is to manage the crisis of the colonial relation by offering critique without strategy, analysis without commitment, and dissent without rupture.

1. The Intellectual: Organic to the Revolution or Curator of Pre-Formed Thought?

Amel establishes the revolutionary criterion:

“The intellectual must be revolutionary or cease to be.” For Amel, thought detached from the revolutionary movement is not neutral; it is either a tool of the masters or a form of mystified retreat. He warns against the “methodological error” of applying “pre-formed thought” to a new reality:

“The application of pre-formed thought to a new reality cannot in the end produce theoretical conceptualisation, i.e. knowledge, of this reality. Rather, this application is the violent insertion of this reality into the fixed moulds of pre-formed thought.”

Kanafani diagnoses the symptom of defeat:

In Thoughts on Change and the “Blind Language”, he identifies the post-1967 Arab intellectual climate as one of “blind language”—where words like revolutionary, socialist, democracy, and freedom are hollowed out, used “according to private understanding—an understanding unagreed upon, rendering them meaningless.” This language, Kanafani argues, is a political weapon used by those who “feel incapable of achieving their goals—or who have no goals at all,” a fog that obscures the revolutionary movement and paralyzes action.

Chomsky as the archetype of “blind language” and applied pre-formed thought:

Chomsky operates entirely within the paradigm Amel condemns. His semi-zionism is a masterclass in “blind language”: using the vocabulary of justice and critique while accepting the foundational myths of settler-colonialism (“Israel’s right to exist”). His anarchism, with its rejection of revolutionary organization and vanguard parties, empties the word “revolution” of strategic content, reducing it to moral protest. While Amel calls for theory to emerge from the colonial relation and Kanafani calls for restoring agreed meanings to words, Chomsky’s project thrives in the ambiguity of the liberal salon, where radical critique is allowed precisely because it is disconnected from a “clear work strategy.” He is not the demystifier, but the architect of a new confusionism: one that dresses strategic surrender in the radical costume of critique.

2. Method: Starting from the Colonial Reality vs. Imposing Abstract Frameworks

Amel’s central methodological injunction:

“We must not begin with Marxism as a pre-formed system of thought that we attempt to apply to our reality. Instead, we must begin with our reality in its own process of formation.” He explains that scientific socialist theory emerged from the historical reality of Western capitalism. To universalize it, it must be reborn through the critique of colonial reality:

“The process of producing Marxist thought as critique of “underdevelopment” is therefore first and foremost a revolutionary rather than theorising process.”

Kanafani’s dialectical triad:

In Political Studies – The Resistance and its Dilemmas, Kanafani elaborates the unity of theory, practice, and organization as the engine of liberation. He identifies the obstacles to this unity in the Arab context: the “rule of fatherhood” (the feudal/patriarchal logic blocking new energy and ideas) and the “blind language.” This leads to a situation where “the absence of a work strategy… nullifies the ability to channel intellectual, political, social, and even military effort toward a goal.”

Chomsky’s methodological failure:

Chomsky’s entire intellectual enterprise is the application of pre-formed anarchist and liberal critique to realities he does not inhabit. His analysis of Palestine starts from abstract principles of “dialogue” and “pragmatism,” not from the concrete structure of the zionist settler-colonial relation. This is precisely the “applied theory” Amel identifies as “idealist and empiricist.” Furthermore, Chomsky’s anti-organizational anarchism reinforces the “rule of fatherhood” in a leftist guise—rejecting disciplined new structures in favor of entrenched, liberal academic hierarchies. His “pragmatic” semi-zionism is a classic product of “blind language,” offering strategically nebulous solutions that obscure the colonial reality.

3. The Colonial Relation: A Structure of Production, Not a Policy Dispute

Amel’s theoretical core—missing from Chomsky’s analysis:

“The colonial relation is a relation of production.” It is not merely economic or political domination, but a structural unity that binds the colonizer and colonized in an unequal, dialectical whole, forming a distinct colonial mode of production. This mode results from a “fusion”—a radical transformation—of capitalist and pre-capitalist modes within the violent framework of colonial domination. “Underdevelopment” is not a natural stage, but an actively produced condition; colonialism is its structural cause.

Kanafani’s historical illustration:

In The 1936–39 Revolt in Palestine, Kanafani does not merely narrate events; he analyzes the colonial relation in motion. He shows how the zionist project fused British imperialism, Jewish capital, and settler-colonial expansion into a single system that dismantled Arab industry, displaced peasants, and created a dependent, fragmented Palestinian society. The revolt failed not because of lack of courage, but because the Palestinian leadership—feudal, religious, and later bourgeois—was itself a product of that colonial relation, incapable of the revolutionary rupture needed to sever it.

Chomsky’s evasion of structure:

Chomsky’s semi-zionism refuses to treat zionism as a colonial relation in Amel’s sense. He sees it as a political conflict amenable to reform, negotiation, and “binational” solutions. This ignores the structural unity Amel describes—a unity that can only be broken by revolutionary severance, not liberal dialogue. Chomsky’s call for “engagement” with Israeli institutions is the epitome of strategic blindness, asking the victim to dialogue within the very relation that produces their erasure.

4. The Bourgeoisie in the Colony: No “Progressive” Ally

Amel’s class analysis demolishes liberal illusions:

He demonstrates that the colonial mode of production generates an “undifferentiated class structure.” The colonial bourgeoisie is “fundamentally a mercantile bourgeoisie… born impotent and paralysed because it was born as a colonial [class].” It is a parasitic, representative, consumer class, structurally tied to imperialism. This creates a “paralysis of the social dialectic.” Class struggle does not manifest as revolutionary struggle but as “class substitution” (e.g., a “national” bourgeoisie replacing a settler bourgeoisie), leaving the colonial mode of production intact.

Kanafani’s historical corroboration:

In his analysis of the 1936 revolt, Kanafani shows how the Palestinian urban bourgeoisie and feudal leaders were objectively tied to British and zionist capital. Their “struggle” was not for liberation, but for “a better position in the colonialist regime.” They raised progressive slogans they had no intention of fulfilling, channeling popular energy into dead ends. This is the “waverining class” in action—the petite bourgeoisie and bourgeois leadership that cannot break from the colonial structure.

Chomsky’s alignment with colonial class interests: